What Slave Ports Can Tell Us About The Untold Stories of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Reading Teju Cole’s Black Paper sparked my interest in the evocative impact of ‘witnessing.’ Teju Cole travels across the globe to capture what it means to witness the humanity of others. Teju Cole’s Black Paper is his personal encounter with the lives of migrants and the human condition in a collection of essays. In one of the essays, he documented his experience stumbling on vessels that symbolize the hazardous passage of migrants to Europe.

These migrants leave their homelands for reasons ranging from political upheaval to economic benefits. “There was no way of telling which, if any, of these boats had tipped its human cargo over into the Mediterranean, which had been intercepted by European authorities, or which had brought its terrified travelers safe to shore.” The sight of the vessels painted in him a vivid image of the horrific experience of their human cargo. “What happened next took me by surprise: I suddenly collapsed to my knees and began to sob. My chest pulsed, my tears flowed, and between those boats with their strong smell of human bodies, I buried my head in my hands, ambushed and astonished by grief.”

400 years of shadow – when did the transatlantic slave trade start?

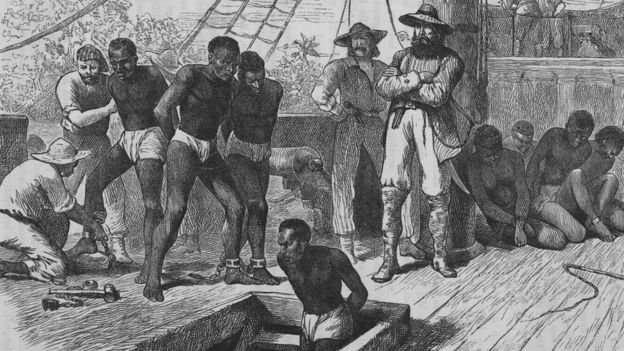

In 400 years, empires rose and fell across Asia and vast civilizations built monuments that defied time. All the while millions of Africans were ripped from their homelands for a forced journey across the Atlantic. The Transatlantic slave trade traces its roots back to the 16th century when European powers with insatiable greed for resources turned their eyes towards West Africa. Portugal initiated the Transatlantic slave trade, transporting enslaved Africans to the Americas for plantation labour. They established forts and trading posts along the West African coast and laid the groundwork for the horrors to come. By the 17th century, other European powers like Spain, France, Britain, and the Netherlands became more involved in the slave trade.

Long before European arrival, inter-tribal warfare and existing power struggles in African communities created a climate ripe for exploitation. European powers exploited these existing divisions and transformed a pre-existing practice into a monstrous trade of unimaginable proportions. Moreover, pre-existing practices of debt slavery and the concept of war captives as spoils of war existed and these created a pool of potential victims. Historical account says that the Transatlantic slave trade lasted for about 400 years and over this period, more than 12 million Africans were taken away as slaves in the New World or Americas. The creation of the African diaspora-the dispersal of black people outside their places of origin on the African continent is also one of the untold stories of the transatlantic slave trade.

The Rise of the Badagry Slave Port

The Dahomey Kingdom held sway over Badagry during the peak of the slave trade. However, Dahomey itself was riddled with internal conflicts and power struggles. This internal strife and competition for resources and European favor created a breeding ground for the slave trade. Dahomean rulers were eager to consolidate power and secure European trade goods. They readily participating in capturing and selling their own people, as well as those from neighboring kingdoms.

In The organization of the Atlantic Slave Trade in Yorubaland, “slave trading and violence were mutually reinforcing. Slaving operations intensified regional interstate rivalry; warfare weakened civilian chiefs, boosted soldiering, and pitted soldiers against their monarchs.” This exploitation of internal divisions by European powers highlights the manipulative tactics that fueled this inhumane trade of humans.

In addition, Badagry’s proximity to the Atlantic Ocean like other African slave ports was a critical factor for European slave traders. According to The Organization of the Atlantic Slave Trade in Yorubaland, Badagry’s notoriety began in the 15th century when Portuguese slave traders arrived through the access to the Atlantic. Consequently, it became a central hub in the Transatlantic slave trade. By the 19th century, Brazil became the major player in the slave trade at Badagry. Sugar plantations in Brazil demanded a large and constant supply of enslaved labor. The International Journal of African Historical Studies recounts that by the 19th century, Brazilians and Cubans had replaced Portuguese slavers and were the primary buyers of slaves at Badagry.

Across The Atlantic: A Legacy Forged in Chains

A Pilgrimage To The Past

The experiences of those forced onto the Badagry slave port were far from monolithic. While some captives were prisoners of war or victims of raids, others were tragically sold into slavery by family members facing desperate circumstances. The skills and backgrounds of enslaved people also influenced their experiences. Even though there are layers of nuance to consider, the core narrative is one of immense suffering. Captured Africans were held in baraccons- cramped holding pens where they awaited transportation across the Atlantic.

I strongly opine that the Badagry slave port tells more untold stories of the Transatlantic slave trade than we care to pay attention to. Historical sites help us acknowledge the tragedy and they serve as reminders, lest we forget. They hold evocative power that transport us into the heart of history. Historical sites hold the keys to connection for the generation that is detached to historical events from centuries ago.

The “Point of No Return,” is a chilling reminder of the brutality they faced. The Mobee Family Slave Relics Museum offers a glimpse into the lives of those enslaved. Shackles of varying sizes and complexities stand as silent witnesses to the experiences of those forced onto the Badagry route. Here, the brutal reality of the trade confronts us and suddenly there are no sanitized portrayals of history materials to shield us.

What It Means To Witness

The visual impact of seeing relics and structures from this chapter of history is deeply moving. Moreover, they put history into context for anyone who cares to know. History transcends the intangible when we walk he paths where Africans marched. This is what it means to witness. And in witnessing, we, like Teju Cole can say “I see this. I see it for what it is.”

TheAdulawo is off on a trip to explore the Badagry slave port beyond the usual tourist experience. Come with us.

- African Art and Its Interconnectedness with Religion

- What Slave Ports Can Tell Us About The Untold Stories of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- A trip to Erin Ijesha Waterfalls (See photos and Video)

- Across The Atlantic: A Legacy Forged in Chains

- Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove: A Journey into Culture

[…] What Slave Ports Can Tell Us About The Untold Stories of the Transatlantic Slave Trade […]